Matching A/D Converter Performance with Application (Part 2)

A fundamental understanding of precision and accuracy and how they relate to ADC specifications enable the designer to quickly choose the right ADC quickly for their application.

In part one of this series, we described a customer problem. They were not getting the accuracy expected in their system even though they thought they selected an appropriate level of ADC performance. We also defined resolution, precision and accuracy.

Now that we have an understanding of precision and accuracy and how they relate to system performance, we will examine the key specifications of an ADC that define precision and accuracy.

Specifications That Define Precision

The parameters that define precision are the same parameters that qualitatively define resolution. Namely, Effective Resolution (bits), Effective Number of Bits (ENOB) and noise (volts). These parameters provide an indication of the repeatability of measurements from the ADC and are typically provided as RMS measurements.

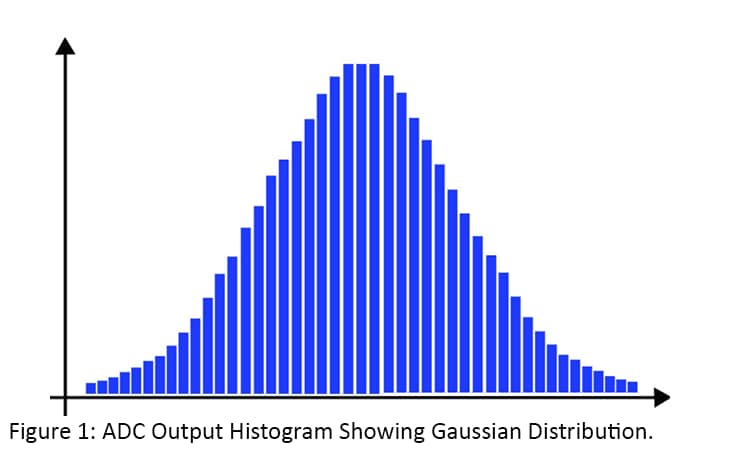

Let’s look at Effective Resolution. It’s measured by taking a histogram of sampled data from the ADC. A fixed voltage is applied to the input of the ADC and the number of occurrences of each output code is plotted. Every ADC has noise and the histogram not only will provide an indication of the noise distribution, but also of the wideband noise. If the wideband noise is white, then the histogram will have a Gaussian distribution, as shown in Figure 1. A Gaussian distribution in the histogram of the ADC indicates the noise is random and digital processing techniques can be used to reduce noise – i.e., improve precision.

Calculating the standard deviation of the histogram defines the RMS noise of the ADC. RMS noise is typically defined as one sigma from the mean and indicates that 68.3% of all ADC values will fall within this range. Peak-to-peak or flicker-free noise is typically defined as 3.3 sigma from the mean and indicates that 99.9% of all ADC values will fall within this range. Some applications use RMS noise as the specification and some applications require peak-to-peak or flicker-free noise. For example, a weigh scale has to display a stable value to very high accuracy, so the noise performance for weigh scales is defines in terms or peak-to-peak or flicker-free noise.

When comparing RMS and peak-to-peak noise in bits, adjust RMS noise by 2.7 bits to convert to peak-to-peak noise. For example, an ADC with 11.7 bits of RMS Effective Resolution will have 9.0 bits of peak-to-peak Effective Resolution.

ENOB and noise are determined in a similar way.

Specifications That Define Accuracy

If you assume the output of an ADC is perfectly linear, then any specification that impacts linearity can be thought of as also impacting accuracy. The key specifications impacting accuracy are offset, gain and linearity.

Offset is a shift in the zero point of the ADC and can be positive or negative.

Gain is a shift in the slope of the ADC output and can be positive or negative.

Linearity is defined in two ways. First, Differential Non-Linearity (DNL) is defined as difference in the size of the code vs. ideal (i.e., code width). If the size of the code is larger than ideal, then it will manifest in the histogram with a higher number of occurrences than expected. If the code size is smaller than ideal, then a smaller number of occurrences will show up in the histogram.

The second aspect of linearity is Integral Non-Linearity (INL). INL is the output code deviation from the ideal slope of an ADC.

It’s important to note that offset and gain errors can readily be removed through calibration to improve accuracy, but linearity errors cannot readily be removed through calibration.

One last note on accuracy specifications: Some ADCs specify Total Unadjusted Error (TUE), which includes offset, gain and linearity. In the TUE calculations, they typically use Root-Sum-Square (RSS) of the contributing error sources to calculate the total error. When relying on TUE to quantify accuracy of the ADC, make sure the datasheet clearly defines how they calculate TUE.

Now that we have a good understanding of the parameters that define precision and accuracy in an ADC, in part three of this series we will look at how and why ADC parameters vary.

To read continued articles on this matter: